What Cochlear Implants Actually Do

When hearing aids stop working, cochlear implants offer a different kind of solution - not louder sound, but direct electrical signals to the brain. These devices don’t fix damaged ears. Instead, they bypass them entirely. For people with profound sensorineural hearing loss - where the hair cells in the cochlea are destroyed - traditional amplification does nothing. Cochlear implants step in where hearing aids fail. They turn sound into coded electrical pulses that stimulate the auditory nerve, letting the brain interpret those pulses as speech, music, or environmental noise.

Unlike hearing aids, which just make things louder, cochlear implants create a new pathway for hearing. The technology has evolved since the first implant in the late 1970s. Today’s systems use between 12 and 22 tiny electrodes, each targeting a specific frequency range in the cochlea. This lets users hear pitch differences - something earlier models couldn’t do well. Modern implants from companies like Cochlear Limited, MED-EL, and Advanced Bionics can even handle MRI scans at 3.0 Tesla without needing surgery to remove internal magnets. That’s a big deal for long-term users who may need imaging later in life.

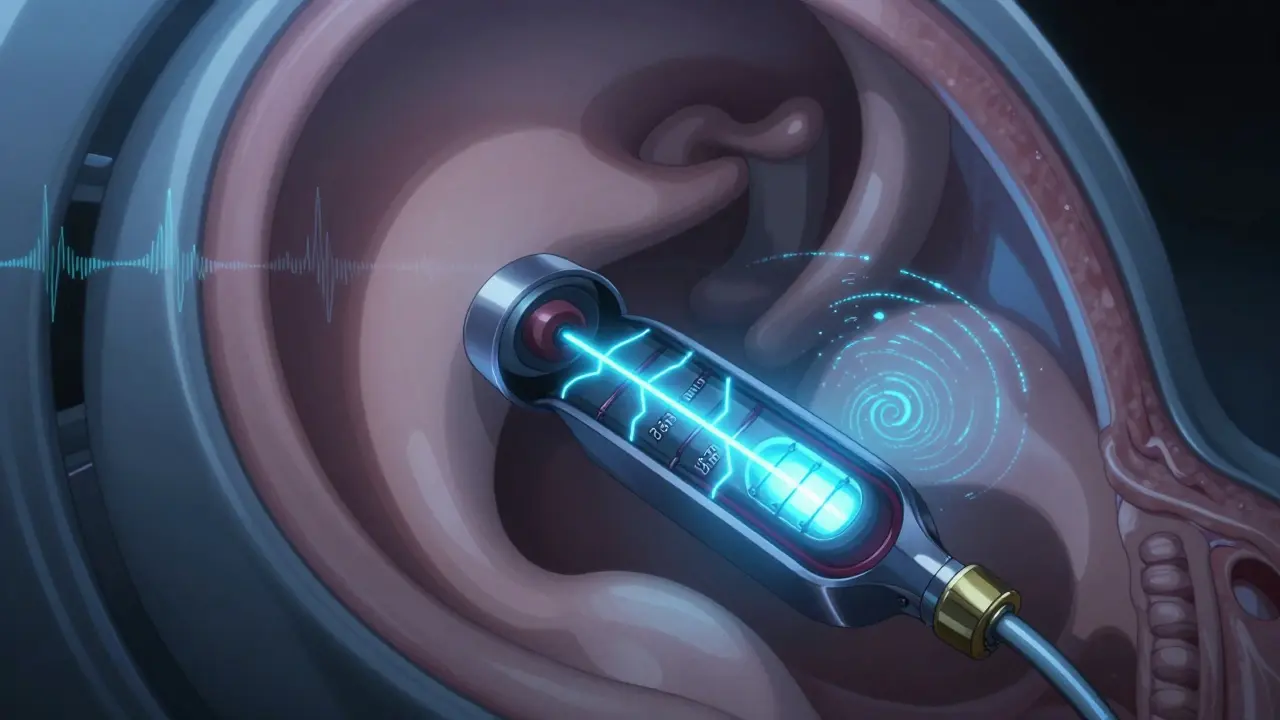

How the Device Works - Inside and Out

A cochlear implant isn’t one piece. It’s two parts working together: external and internal. The external part sits behind the ear. It has a microphone that picks up sound, a processor that turns it into digital signals, and a transmitter coil that sends those signals through the skin. The internal part is surgically placed under the skin behind the ear. It includes a receiver-stimulator - about the size of a small coin - and a thin, flexible electrode array that snakes into the cochlea.

The electrode array is key. It’s typically 16 to 31.5 millimeters long and has 12 to 22 contact points spaced less than a millimeter apart. Each contact delivers tiny electrical pulses - between 50 and 600 microamperes - to different parts of the cochlea. These pulses mimic how natural hearing works: low frequencies are stimulated near the top of the cochlea, high frequencies near the bottom. The brain learns to interpret these patterns over time. Transmission between the external and internal parts happens wirelessly, using radio frequencies between 5 and 10 MHz, with a range of just half a centimeter to two centimeters. No wires. No holes. Just precise, invisible communication.

Who Qualifies for an Implant

Not everyone with hearing loss is a candidate. Cochlear implants are meant for those with severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss who get little to no benefit from hearing aids. In the U.S., the FDA requires that adults have speech recognition scores below 50% on standardized tests, even with the best hearing aids. For children, the bar is lower: if they’re not developing speech and language at a normal pace, and hearing aids aren’t helping, an implant may be recommended.

Candidates used to be mostly adults who lost hearing after learning to speak. Now, the list has expanded. Infants as young as 9 months old can get implants. Adults with single-sided deafness, and even some with auditory neuropathy, are now being considered. The key is whether the auditory nerve is intact. If the nerve is damaged or missing, an implant won’t work. That’s where bone conduction devices might be a better option.

Insurance coverage usually requires proof of hearing loss severity - pure-tone averages over 70 dB HL - and documented failure of hearing aids. Many people don’t realize they qualify until they’ve struggled for years. If you’ve been told, “You’re too deaf for hearing aids,” it’s time to ask about cochlear implants.

The Surgery - What Happens in the Operating Room

The surgery takes about two hours and is done under general anesthesia. Surgeons make a 4 to 6 centimeter incision behind the ear. Then comes the mastoidectomy - removing part of the mastoid bone to reach the middle ear. The facial nerve runs right next to this area, so surgeons use real-time monitoring to avoid damaging it. If the nerve twitches at a current above 0.05 milliamperes, the surgeon knows they’re too close.

Next, the surgeon opens the cochlea. This can be done through the round window - a natural opening - or by drilling a small hole called a cochleostomy. The electrode array is then gently threaded into the scala tympani, the fluid-filled chamber of the cochlea. The receiver-stimulator is placed in a shallow pocket carved into the skull bone. The incision is closed, and the patient usually goes home the same day or the next.

Complications are rare - under 5% in experienced centers - and major ones like facial paralysis happen in less than 1% of cases. Most people feel mild soreness for a few days. The scalp around the implant may feel numb for weeks, but that fades. Around 95% of implants are confirmed working during surgery using direct testing in the operating room.

Recovery and Activation - The Real Work Begins

Healing takes time. The implant isn’t turned on right away. Most patients wait 2 to 4 weeks for swelling to go down and tissues to settle. Activation is a big moment. When the external processor is first connected, the sound is strange - robotic, metallic, like a cartoon character. That’s normal. The brain hasn’t learned to interpret these signals yet.

Over the next few months, the device is fine-tuned in multiple programming sessions. Audiologists adjust volume levels, pulse rates, and which electrodes are active. For children, this is paired with intensive auditory-verbal therapy. A child implanted before age 2 often develops speech close to normal levels. Those implanted after age 7 usually need more time and support. Adults, especially those who lost hearing later in life, often adapt faster because their brains remember what speech sounds like.

Most users report major improvements in speech understanding within 3 to 6 months. Studies show 80% of adult recipients can understand 80% or more of sentences in quiet rooms - something most couldn’t do even with powerful hearing aids. But it’s not perfect. Background noise still makes things hard. In noisy places, understanding can drop to 30-50%. Music remains challenging. Many users say they can recognize a melody, but the tone and richness are lost.

Long-Term Outcomes and Limitations

These devices aren’t a cure, but they’re life-changing. Ninety percent of adult recipients report better communication, and many say they’ve reconnected with family, returned to work, or stopped feeling isolated. One recipient described hearing his granddaughter laugh for the first time after 15 years of silence. That’s not a statistic - that’s real.

But there are trade-offs. About 5-10% of implants fail over time and need revision surgery. A small number - 2-3% - deal with ongoing dizziness or ringing in the ears. Some people never fully adapt. The longer someone has been deaf before implantation, the harder it is for the brain to relearn hearing. That’s why early intervention in children is so critical.

Longevity is good. The internal device is designed to last 20 to 30 years. The external processor? That’s upgradeable. As new sound-processing tech comes out - like AI-driven noise filters - you can swap the external unit without another surgery. That’s a huge advantage over older models.

What’s Next for Cochlear Implant Technology

The field is moving fast. New electrode designs aim to reduce scar tissue buildup around the implant, which can block signals over time. Some researchers are testing drug-coated electrodes that release anti-inflammatory agents directly into the cochlea. Hybrid implants - combining acoustic amplification for low pitches with electrical stimulation for high ones - are helping people who still have some natural hearing in the lower frequencies.

Miniaturization is another big trend. Next-gen processors are getting smaller, more powerful, and better at filtering noise. Some prototypes use machine learning to automatically adjust settings based on the environment - like turning up speech in a crowded room without user input. MRI compatibility is now standard in top models, but future implants may eliminate magnets entirely to avoid any interference.

Accessibility is improving too. More countries now cover cochlear implants under public health systems. In the U.S., over 324,000 people have them worldwide - and that number keeps rising. The goal isn’t just to restore hearing. It’s to restore connection.

Can cochlear implants restore normal hearing?

No. Cochlear implants don’t restore natural hearing. They provide a substitute - electrical signals that the brain learns to interpret as sound. Most users describe the initial sound as mechanical or robotic. With time, the brain adapts, and speech becomes clearer, but music and background noise often still sound unnatural. The goal is functional hearing, not perfect replication.

Are cochlear implants only for children?

No. While early implantation in children leads to the best speech outcomes, adults of any age can benefit. Many adults who lost hearing later in life regain the ability to understand conversations, use the phone, and enjoy social settings. In fact, adults often adapt faster than children because their brains already know what speech sounds like.

How long does it take to hear properly after surgery?

Activation usually happens 2 to 4 weeks after surgery. Most people notice improvement in speech understanding within 3 to 6 months. But full adaptation can take up to a year, especially for children or those who’ve been deaf for a long time. Consistent use and therapy are essential - it’s not just about the device, it’s about training the brain.

Can you swim or shower with a cochlear implant?

The internal part is sealed and waterproof, so you can swim and shower safely. But the external processor isn’t. You need to remove it before getting wet. There are waterproof covers and accessories available for swimming or rainy days, but the processor itself must stay dry. Always check with your manufacturer’s guidelines.

Do cochlear implants need to be replaced?

The internal implant is designed to last 20-30 years and rarely needs replacement unless it fails. Most issues are with the external processor, which can be upgraded as new technology comes out - no surgery needed. If the internal device does fail, replacement surgery is possible, but it’s more complex than the first implant.

Is there an age limit for getting a cochlear implant?

No. There’s no upper age limit. People in their 80s and 90s have successfully received implants and reported improved quality of life. The deciding factors are overall health, the condition of the auditory nerve, and whether the person can participate in rehabilitation. Age alone doesn’t disqualify someone.

Stacey Smith

This is why America leads in medical innovation. No other country gives people this kind of second chance.

Meina Taiwo

In Nigeria, access is still limited, but NGOs are starting to partner with hospitals. Early screening saves years of therapy.

Cameron Hoover

I had my implant at 42 after 15 years of silence. The first time I heard my dog bark? I cried in the grocery store.

It’s not perfect - music still sounds like robots arguing - but I can talk to my grandkids now. That’s everything.

Ben Warren

The clinical literature consistently demonstrates that cochlear implantation constitutes a neurosensory intervention predicated upon the neuroplasticity of the central auditory pathways. However, the ethical implications of neural interface technologies remain under-regulated by federal oversight bodies.

Moreover, the commercial monopolization of implant hardware by three multinational corporations - Cochlear Limited, MED-EL, and Advanced Bionics - creates significant barriers to equitable access, particularly within underserved populations. The FDA’s 50% speech recognition threshold, while statistically defensible, lacks longitudinal validation for non-native English speakers and may perpetuate diagnostic inequities.

Adrian Thompson

They say it’s a miracle. I say it’s a government-mandated chip. You think they don’t track what you hear? You think they don’t control the frequencies?

Next thing you know, they’ll be turning your implant off if you say the wrong thing. And don’t get me started on the magnets - they can be activated remotely. That’s not medicine. That’s surveillance.

Southern NH Pagan Pride

ok so i read this whole thing and like... the implants are fine i guess but like... what if the brain just... forgets how to hear? like what if the signals are just... noise? and what if the company stops updating the software? and what if the gov uses it to spy? i mean... they already put chips in vaccines right?

also the word 'cochlea' sounds like a cult name

Jackie Be

I got mine at 19 and now I can hear my mom say I love you without crying every time - and yes I cried when I heard rain on the roof for the first time

it’s not magic but it’s the closest thing we got to it and if you’re hesitating just do it you’ll thank yourself later

Orlando Marquez Jr

In Japan, cochlear implantation is integrated into the national healthcare system with standardized post-operative rehabilitation protocols. The cultural emphasis on auditory social integration results in higher usage rates among elderly populations. Notably, the absence of commercial advertising for implant manufacturers reduces patient anxiety regarding technological obsolescence. This model warrants serious consideration in Western contexts.