When you take a pill, does it matter if you swallowed it with breakfast or on an empty stomach? The answer isn’t just about stomach upset-it’s about whether the medicine actually works the way it’s supposed to. This same question shows up in fitness labs, pharmaceutical trials, and even in the routines of elite athletes. The difference between fasted state testing and fed state testing isn’t a minor detail. It’s a fundamental shift in how your body processes everything from medication to fuel during a workout.

What Fasted and Fed States Actually Mean

Fasted state means no food for at least 8 to 12 hours. Water is allowed. Coffee without sugar or cream? Usually okay. This is the condition used in most blood tests-cholesterol, glucose, liver enzymes-because food can throw off the numbers. Fed state means you’ve eaten a meal, typically within the last 2 to 4 hours. In drug trials, that meal isn’t just any snack. It’s a standardized high-fat, high-calorie meal: about 800-1,000 calories, with 500-600 of those coming from fat. Think bacon, eggs, cheese, avocado, buttered toast. Not a banana and yogurt.

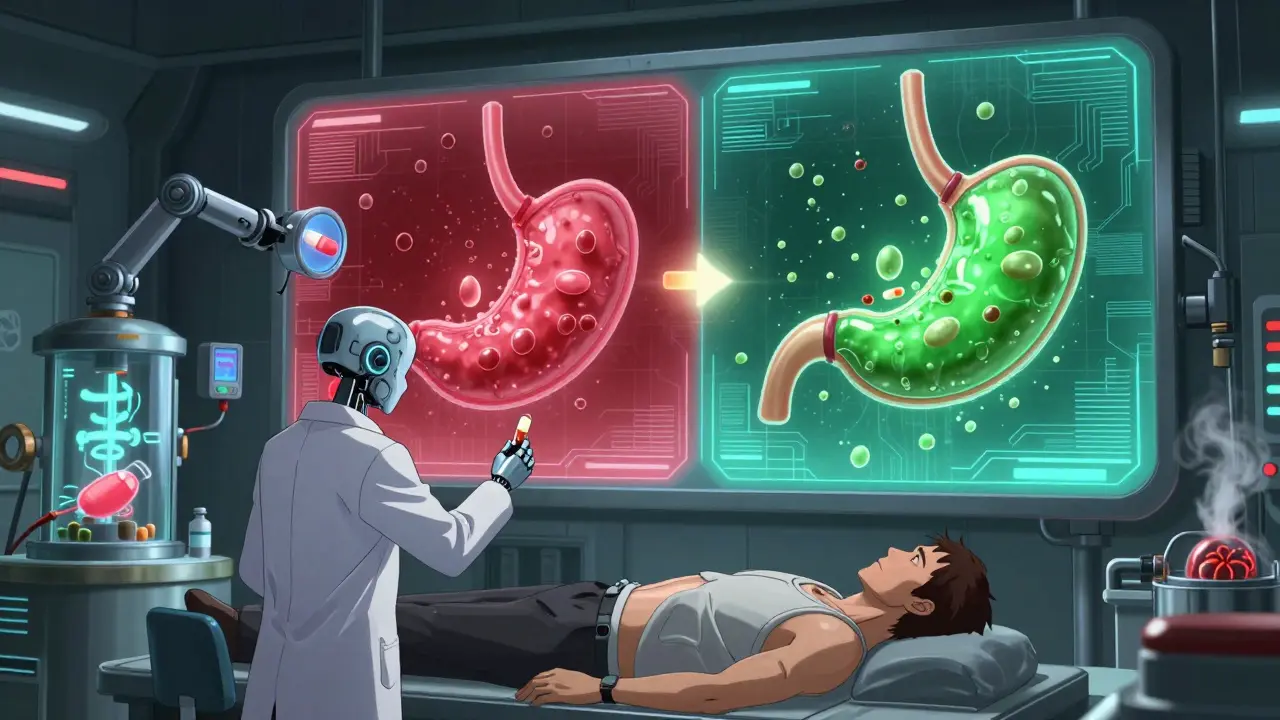

These aren’t arbitrary labels. They represent two completely different physiological environments. In the fasted state, your body is running on stored energy. Insulin is low. Fat breakdown (lipolysis) is high. Free fatty acids flood your bloodstream-up to 50% more than when you’re fed. Your stomach is empty, pH is around 2.5, and food moves through quickly-about 14 minutes on average. In the fed state, insulin spikes. Your body is busy storing nutrients. Gastric emptying slows to nearly 80 minutes. Stomach acid drops to a median of 1.5, and pressure inside your gut climbs consistently above 240 mbar. These aren’t small differences. They change how drugs dissolve, how nutrients absorb, and how your muscles burn fuel.

Why Drug Companies Test Both

The pharmaceutical industry doesn’t test both states because it’s thorough. They do it because the law requires it. The FDA and EMA both mandate that any new oral drug must be tested under both fasted and fed conditions. Why? Because food can make a drug work better-or worse-by a huge margin.

Take fenofibrate, a cholesterol-lowering drug. When taken with food, its absorption jumps by 200-300%. Without food, it barely gets into your system. On the flip side, griseofulvin, an antifungal, sees its absorption drop by 50-70% when eaten with a meal. If you only tested it in a fasted state, you’d think it worked fine. But give it to someone who eats breakfast, and they get almost no benefit. That’s dangerous.

That’s why the FDA now requires dual-state testing for nearly all oral medications. A 2019 analysis of 1,200 new drug applications found that 35% of drugs had clinically significant food effects. That means one in three pills you take could behave completely differently depending on whether you ate. The European Medicines Agency tightened this even further in 2024, requiring continuous glucose monitoring during fed-state trials to track how real-time metabolism affects drug absorption.

And it’s not just about absorption. Food changes stomach pH, slows gut movement, and alters blood flow to the intestines. These changes affect how quickly and how much of the drug enters your bloodstream. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where the difference between a dose that works and one that’s toxic is tiny-this isn’t just important. It’s life-or-death.

How This Applies to Exercise and Fitness

The same principles apply to how your body handles exercise. In fitness research, fasted training means working out after 8-12 hours without food. Fed training means eating a meal 1-4 hours before, usually with 1-4 grams of carbs per kilogram of body weight. That’s about 70-280 grams of carbs for a 70kg person-think two bananas, a bowl of oatmeal, or a bagel with peanut butter.

Studies show fed-state exercise improves endurance performance by about 8.3% in longer sessions (over 60 minutes). If you’re running a marathon or cycling for hours, eating beforehand gives you the glycogen fuel you need to keep going. But for short, high-intensity workouts-like 20-minute HIIT or strength training-there’s no measurable benefit. Your body has enough stored glycogen to power through.

Fasted training, on the other hand, ramps up fat burning. Free fatty acid levels rise 27.6% more after a fasted workout compared to a fed one. It also turns on genes like PGC-1α, which boosts mitochondrial growth-the tiny powerhouses in your cells that produce energy. This is why some people swear by fasted cardio for fat loss.

But here’s the catch: fasted training can reduce your high-intensity output by 12-15%. If you’re lifting heavy, sprinting, or doing CrossFit, you’ll likely feel weaker, slower, and more fatigued. One 2021 study found that over six weeks, fasted and fed training groups lost the same amount of body fat-even though fasted participants burned more fat during the workout. The body adjusts. What matters most over time isn’t what happens in a single session, but consistency.

Who Should Train Fasted? Who Should Eat First?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. It depends on your goals, your body, and your schedule.

- If you’re trying to improve metabolic health-lower insulin resistance, reduce belly fat, or manage prediabetes-fasted training can help. Fourteen randomized trials show 5-7% better improvements in insulin sensitivity with fasted workouts.

- If you’re an athlete competing in endurance events, eating before training is non-negotiable. Ultramarathoner Scott Jurek credits fed-state training for his ability to sustain high intensity over long distances.

- If you’re doing strength training or high-intensity intervals, fed state gives you the energy to push harder and recover faster.

- If you feel dizzy, weak, or nauseous when you train on an empty stomach, don’t force it. Your body is telling you it needs fuel.

Professional athletes are split. Rich Froning, a four-time CrossFit Games champion, trains most of his metabolic sessions fasted to train his body to burn fat efficiently. But he’s also genetically wired for endurance and has spent years adapting. Most people aren’t.

A 2022 Reddit survey of 1,247 fitness enthusiasts found 68% performed better when fed. But in a r/ketogains group of 853 people focused on fat loss, 42% preferred fasted training. Yet 31% reported dizziness, and 22% said their workouts felt weaker. Individual variation is huge.

The Hidden Variables Nobody Talks About

It’s not just about eating or not eating. The whole context matters.

In research, scientists control for sleep (minimum 7 hours), hydration (urine specific gravity under 1.020), and even activity the day before (no intense exercise 24 hours prior). Why? Because lack of sleep raises cortisol, which affects fat metabolism. Dehydration alters blood volume and drug concentration. A hard workout the day before depletes glycogen stores, making fasted training even harder.

And then there’s genetics. A 2022 study found that variations in the PPARGC1A gene explain 33% of why some people respond better to fasted training than others. Two people can do the exact same workout, eat the same meals, and get completely different results. That’s why blanket advice like “always train fasted for fat loss” is misleading.

Even ethnicity plays a role. A 2022 study showed Asian populations have 18-22% slower gastric emptying in the fed state compared to Caucasian populations. That means a drug or nutrient absorbed quickly in one group might linger longer-or not absorb well-in another. That’s why the FDA now requires fed-state trials to include diverse ethnic groups.

Practical Takeaways: What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a lab to apply this knowledge. Here’s how to use it:

- For medication: Always follow the label. If it says “take on an empty stomach,” wait 2 hours after eating or take it 1 hour before. If it says “take with food,” don’t skip the meal. Your doctor didn’t say it lightly.

- For endurance training: Eat a carb-rich meal 2-4 hours before long sessions (over 90 minutes). A banana, toast, or oatmeal works.

- For strength or HIIT: Eat something light 30-60 minutes before. A small protein shake or a handful of nuts can make a difference.

- For fat loss or metabolic health: Try one or two fasted workouts per week-especially low-intensity steady-state cardio like walking or cycling. Don’t force it if you feel awful.

- Track how you feel: Keep a simple log: what you ate, when you trained, how you felt, and how hard you worked. After a few weeks, patterns will emerge.

The bottom line? Fasted and fed states aren’t right or wrong. They’re tools. The key is matching the tool to the job. Your body responds differently depending on whether it’s hungry or full. Ignoring that difference-whether you’re taking a pill or going for a run-means you’re leaving performance, safety, and results on the table.

What’s Next for Fasted and Fed Research

The field is moving toward personalization. Instead of telling everyone to train fasted or fed, researchers are now looking at genetic markers, gut microbiome profiles, and real-time glucose monitoring to predict who benefits from which state. Companies are already developing wearable sensors that track your metabolic response to food and exercise in real time.

Pharmaceutical testing is getting even stricter. By 2025, regulators may require fed-state trials to include multiple meal types-not just high-fat meals-to reflect how people actually eat around the world. One-size-fits-all meals are being replaced by culturally relevant, real-world food patterns.

For fitness, the future isn’t about choosing one state over the other. It’s about periodizing them. Train fasted on recovery days. Train fed on heavy lifting or race simulation days. Let your goals and your body guide you-not a trend.

Does fasting before a workout burn more fat?

Yes, during the workout itself, fasted exercise increases fat burning by about 27.6% compared to fed exercise. However, over time, total fat loss is similar between fasted and fed groups. Your body adapts. What matters more is consistency, calorie balance, and recovery-not whether you trained on an empty stomach.

Should I take my medication with food or on an empty stomach?

Always follow the instructions on the label or from your doctor. Some drugs, like fenofibrate, need food to be absorbed properly. Others, like certain antibiotics, lose effectiveness if taken with food. Taking a drug incorrectly can mean it doesn’t work-or causes side effects. When in doubt, ask your pharmacist.

Can fed-state testing affect how well a drug works for different people?

Absolutely. Studies show that people of Asian descent often have slower gastric emptying in the fed state, meaning drugs may stay in the stomach longer and absorb differently than in Caucasian populations. That’s why new drug trials now include diverse ethnic groups. What works for one person might not work the same for another.

Is fasted training better for weight loss?

Not necessarily. While fasted training increases fat burning during the workout, studies over 6-12 weeks show no difference in total fat loss between fasted and fed groups. The key to losing weight is burning more calories than you consume over time. Fasted training might help some people stick to their routine, but it’s not a magic trick.

Why do some athletes train fasted and others don’t?

It depends on their sport and goals. Endurance athletes like ultramarathoners often train fed to sustain high intensity. Strength and power athletes eat before training to maximize performance. Some athletes train fasted to improve fat-burning efficiency, especially during low-intensity sessions. It’s a strategy, not a rule. Personal preference, genetics, and training phase all play a role.

Do I need to test both fasted and fed states if I’m healthy?

Not unless you’re in a clinical trial or taking a medication with known food interactions. But understanding how your body responds to food and exercise can help you optimize your routine. If you feel weak during morning workouts, try eating a small snack. If you feel sluggish after meals, experiment with timing. Small tweaks based on your own experience can make a big difference.

Juan Reibelo

Wow. Just... wow. This is the most thorough breakdown of fasted vs. fed I’ve ever read. I’ve been taking my statin on an empty stomach for years because the bottle said so-but now I’m wondering if I’ve been sabotaging myself. I’m going to check with my pharmacist tomorrow. Thanks for the clarity.

Gina Beard

Food isn’t just fuel. It’s a modifier. A silent architect of biology. You don’t control your metabolism-you negotiate with it. And most people don’t even know they’re in a treaty they never signed.

Josh McEvoy

so like… if i take my adderall with a bacon cheeseburger… does it turn into a super pill?? 😱🤯

Heather McCubbin

Of course the FDA requires dual testing. They don’t care if you live or die-they care if the drug looks good on paper. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know food changes everything. They want you to take it the same way every day. Easy. Predictable. Profitable.

Tiffany Wagner

I’ve been doing fasted cardio for months and felt great until last week. I passed out on the treadmill. Turns out I was dehydrated and didn’t sleep enough. The article nailed it-context matters. I’m going to start tracking sleep and hydration too.

Dolores Rider

They’re lying. They’ve been hiding this for decades. The same companies that told us fat was evil now say you need fat to absorb meds? It’s all a scam. The government, the FDA, the gyms-they all profit from your confusion. Wake up. The truth is in the gut.

Vatsal Patel

So let me get this straight. In India, we eat spicy food with medicine all the time. But the FDA tests with bacon and butter? That’s like testing a motorcycle with a bicycle helmet. Your science is colonial. And yes, I’ve taken antibiotics with chai and lived. Just saying.

Sharon Biggins

you’re not alone if you feel weird doing fasted workouts. i used to force it because i thought it was ‘more disciplined’ but then i tried eating a banana before and suddenly i could lift heavier and not feel like i was going to pass out. your body knows what it needs. listen to it. 💪❤️

John McGuirk

They’re testing drugs with high-fat meals because they want you to stay sick. If you absorbed everything perfectly, you’d get better faster. And then who buys the next pill? The system is rigged. I stopped taking my meds last year. I’m healthier now. No pills. Just garlic and sunlight.

lorraine england

my mom takes metformin and always eats a small snack with it-she says it stops the stomach cramps. i never thought about why until now. this makes so much sense. thanks for writing this. i’m going to share it with my whole family.

Darren Links

So now we’re supposed to believe that American bacon is the gold standard for drug testing? What about the rest of the world? You think they care about your high-fat meal in a country where rice is the main dish? This is cultural imperialism disguised as science.